Food | Cookbooks | Podcast

Who first started collecting recipes into cookbooks? Do cookbooks have a future in a world full of online recipes? And can cookbooks tell us anything about what people are actually eating, or are they simply aspirational food porn? This episode, we explore the past, present, and future of cookbooks, from cuneiform tablets to Hail Marys, with the help of two of our favorite cookbooks authors—and Gastropod fans—Nigella Lawson and Yotam Ottolenghi. |

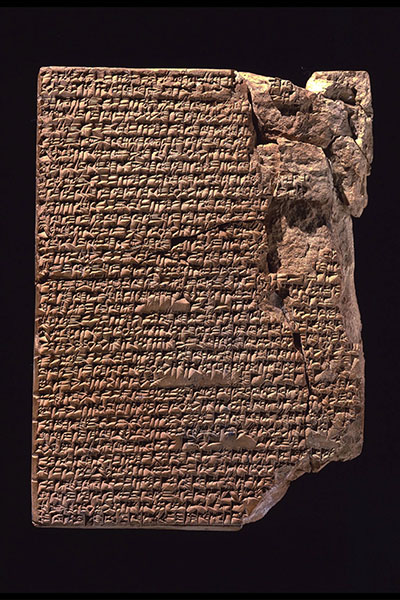

| The oldest known culinary recipes. YBC 4644 from the Old Babylonian Period, ca. 1750 BC, via Yale University Library. |

According to Henry Notaker, journalist and author of A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page Over Seven Centuries, the first cookbook that archaeologists have discovered is 3,700 years old. It consists of 35 recipes written on clay tablets, and its recipes are thought to have been intended for gods rather than humans. Still, it demonstrates that humans have been collecting cooking instructions for millennia. A few things have remained the same for much of the cookbook's history: they are still anthologies of imaginary meals, often fueled more by aspiration and desire than the reality of what's for dinner, and they still promise an almost alchemical transformation of raw ingredients into status and well-being.

Others aspects of today's cookbooks are much more recent. Such seemingly essential formatting elements as a separate ingredients list only became standard relatively recently. Meanwhile, the content, authorship, and user base of cookbooks have shifted dramatically in response to technological innovation and social change. Notaker points to the first German recipe to include bananas as a sign that the exotic fruit was becoming available in Europe: published in 1913, it recommends frying the fruit with marjoram, like a sausage. (The recipe was literally titled "banana sausage.") Meanwhile, Megan Elias, author of Food on the Page: Cookbooks and American Culture, traces the introduction of refrigeration and mass transportation through the strawberry's rise to glory in early twentieth-century recipes. Finally, in a world where more recipes are published online everyday than anyone could hope to cook in a week, we ask: what is the role of the cookbook today—and what might it become in the future? Listen in this episode for more of the surprising story of cookbooks, including men in drag and Norwegian drinking songs, as well as cookbook authors Nigella Lawson and Yotam Ottolenghi's tales of writing their very first cookbooks.

Episode Notes

Yotam Ottolenghi

Yotam Ottolenghi is an Israeli-British chef and restaurateur, and the author of many of our favorite cookbooks, including, most recently, Sweet: Desserts from London's Ottolenghi.Nigella Lawson

Nigella Lawson is a British food writer and T.V. personality, and the author of our other favorite cookbooks, including, most recently, At My Table: A Celebration of Home Cooking.Henry Notaker and A History of Cookbooks

Henry Notaker is a Norwegian journalist and author of A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page Over Seven Centuries.The First Recipe Book

Tablets YBC 4644, YBC 8958, and YBC 4648 together contain 35 recipes from ancient Mesopotamia. According to Henry Notaker, they form the earliest "cookbook" yet discovered, though they consist primarily of lists of ingredients and are thought to be instructions for dishes to be served in religious ceremonies, rather than for dinner. In 1995, French historian Jean Bottéro published translations of the recipes in a book titled Textes Culinaires Mésopotamiens; journalist Laura Kelley published her interpretations online here, if you'd like to have a go at preparing them yourself.Link to podcast: